1891| Doctor Thomas Neill Cream

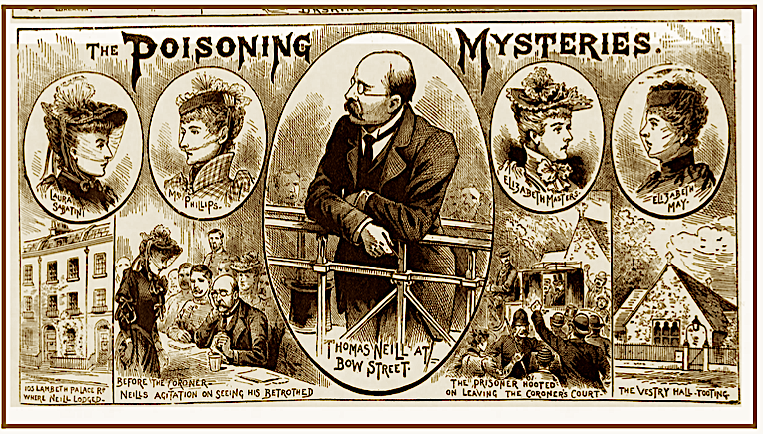

The Lambeth Poisoner

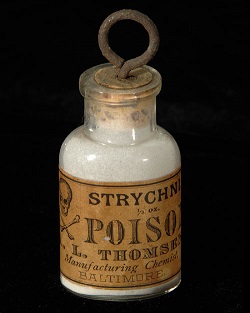

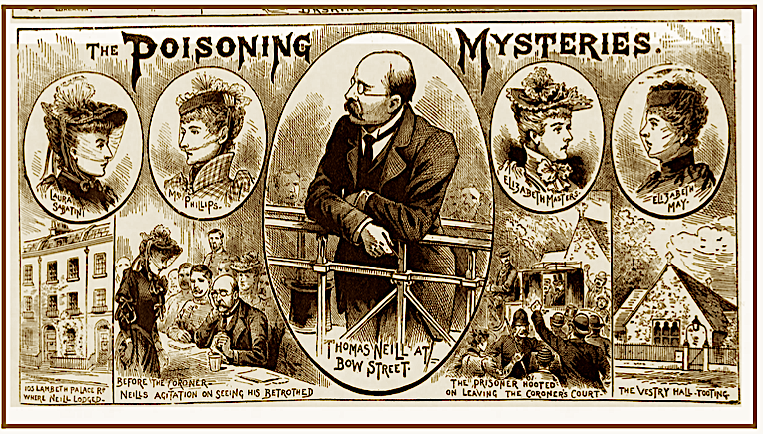

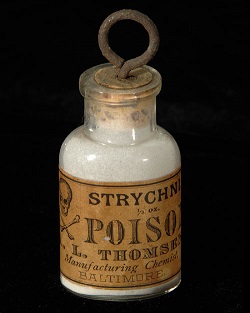

At approximately 7:30pm on the 13th October 1891, a young prostitute, Ellen Donworth, aged nineteen, was plying her trade along Waterloo Road when she staggered and collapsed on the pavement. A man called James Styles ran to her and half-carried her to her nearby lodgings in Duce Street, off Westminster Bridge Road. She was in agony, but was able to gasp that a tall gentleman with cross eyes and a silk hat had given her some ‘white stuff’ to drink from a bottle when she met him earlier that evening in the York Hotel on Waterloo Road. She died on the way to the hospital. A post-mortem revealed strychnine in her stomach. A jeweller’s traveller was later arrested in connection with her death but soon released.

The coroner officiating at her inquest, Mr G.P.Wyatt, received a letter on the 19th October from ‘G. O’Brien, Detective’. It said. ‘I am writing to say that if you and your satellites fail to bring the murderer of Ellen Donworth, alias Linell…to justice, I am willing to give you such assistance as will bring the murder to justice, provided you government is willing to pay me £300,000 for my services. No pay if not successful’

Another letter, from ‘H.Bayne Barrister’ was sent to Mr W. F. D. Smith, MP a member of the newsagent family, W. H. Smith and Son Limited. The letter said that two incriminating letters from Ellen Donworth had been found in her possession and the writer had offered his services as ‘counsellor and legal adviser’.

A Week after her death, on the 20th October, the cries of another prostitute, twenty-six year old Matilda Clover, roused the house of ill-fame in Lambeth Road, run by mother Philips, in which she had a room. Matilda was also a mother of a two-year-old boy. Writhing and screaming in agony she managed, before she died to say that a man called Fred had given her some white pills. A servant-girl, Lucy Rose, recalled seeing this Fred, who was tall and moustached, aged about forty, and wore a tall silk-hat and a cape. Matilda’s death was attributed to DTs caused by alcoholic poisoning – not unreasonably, as she drank heavily, morning, noon and night. She was buried in a pauper’s grave in Tooting.

A month later, a distinguished doctor in Portman Square, Dr William Broadbent, was astonished to get a letter on the 28th November 1891 from ‘M. Malone’ accusing him of the murder of Matilda Clover, who had been ‘poisoned by strychnine’, and threatening him exposure unless he paid £2,500. In December, Countess Russell, a guest at the Savoy Hotel, received a blackmail note naming her husband as Matilda’s murderer

Then the poisoner’s epistles and murderous activities suddenly ceased. He had fallen in love and had become engaged.

Several months later, on the 12th April 1892, two more young prostitutes died in agony. They were Emma Shrivell and Alice Marsh, who both lived in second-floor rooms in 118 Stamford Street, a house of ill-fame kept by a woman called Vogt. Before they died the girls told a policeman that a doctor called Fred had visited them that night, and after a meal of bottled beer and tinned salmon he had given each of them three long thin pills. He was stoutish, dark, bald on top of his head, wore glasses, and was about 5ft 8 ins or 9ins. The policeman, PC Cumley, recalled seeing such a man leave the building at 01:45am.

It was established later both prostitutes had been poisoned with strychnine, and the newspapers speculated wildly about the identity of the Lambeth Poisoner. Could he be Jack the Ripper, whose identity had suddenly ceased in 1888?

‘What a cold-blooded murder!’

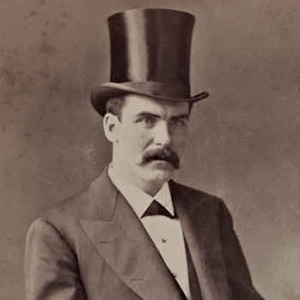

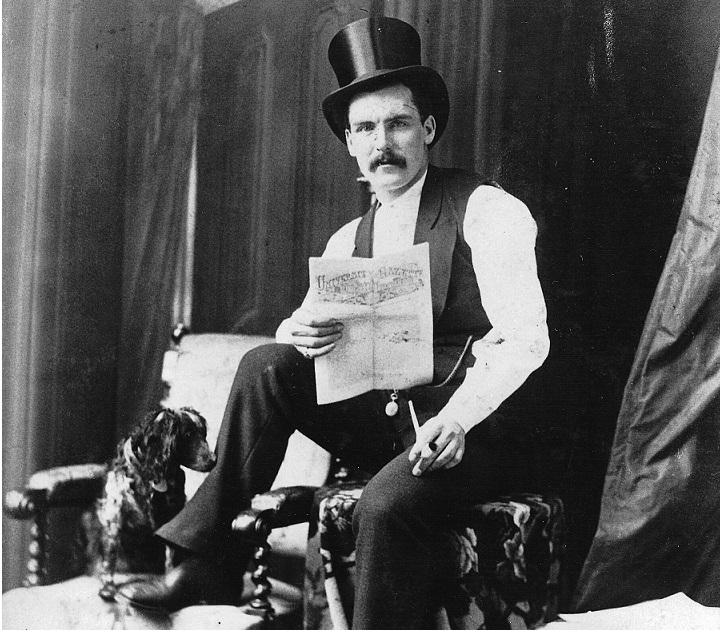

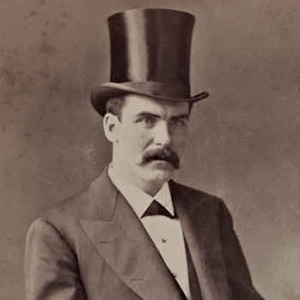

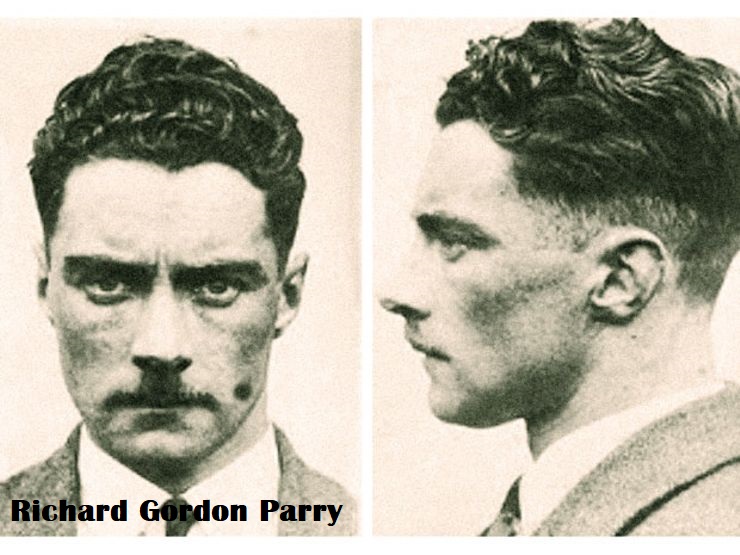

‘What a cold-blooded murder!’ exclaimed Dr Neill (Thomas Neill Cream called himself) when he read about the inquest on the two girls in a newspaper on Easter Sunday on the 17th April. He told his landlady’s daughter, Miss Sleaper, that he was determined to bring the miscreant to justice. A tall, bald, cross-eyed, broad-shouldered man who wore tall hats and glasses specially made for him in Fleet Street, Dr Cream had rented a second-floor room in 108 Lambeth Place Road since 9th April, after returning to London from Canada. He had stayed there before, between 07th October the previous year and January, when he took a trip to America. In December, he had become engaged to a girl called Laura Sabbtini, who lived with her mother in Berkhamsted. He made out a will in her favour. On Christmas Day he had dined with the Sleapers in his lodgings, joined in their family entertainments, singing hymns in the evening and playing the zither. He was no trouble, going out at night alone to places of entertainment and debauchery.

In those days that area south of the River Thames between Westminster and Waterloo bridges was thronged with pubs, theatres, prostitutes and other amusements. There was Astley’s circus and playhouse; the surrey, with its rowdy melodramas (gallery, 6d; pit 1s); the Canterbury music-hall, with its picture gallery; and the Old Vic, which had, however, become respectable, with blameless programmes and temperance bars, since Emma Cons became a director in 1880.

Cream was ready on his night-time jaunts, it seems, to converse with any man about plays or music, but his favourite topic was women, about who he spoke crudely. He would describe his tastes and pleasures and exhibit a collection of indecent pictures which he carried about him.

An article published in the St James Gazette said he dressed with taste and care and was well-informed. It continued: ‘His very strong and protruding under-jaw was always at work chewing gum, tobacco or cigars…He never laughed or even smiled…He occasionally said “Ha-ha!” in a hard, stage-villain-like fashion, but no amount of good nature could construe it into an expression of geniality.’ The article also referred to his ‘never-ending talk about women’ and referred to the fact that he swallowed pills which he said had aphrodisiac properties.

In the same lodging house as Dr Cream was a young medical student from St Thomas’s Hospital, Walter Harper. Cream told Miss Sleaper most forcibly that it was Harper who had killed the girls. The police had proof, he said, and the girls had been warned by letter. Miss Sleaper, a girl of spirit, replied that he must be mad. Unabashed, Cream wrote to young Harper’s father, a doctor in Barnstable, accusing his son of the murders and offered to exchange such evidence as he had for £1,500. He wrote; ‘The publication of the evidence will ruin you and your family forever, so that when you read it you will tell no one to tell you that it will convict your son…if you do not answer me at once, I am going to give evidence to the coroner at once.’

Cream was just as outspoken with a drinking acquaintance, an engineer named Haynes, who also happened to be a private enquiry agent. Haynes showed great interests in what Cream had to say, and in due course disclosed all he had discovered to Police Sergeant McItyre of the CID. Sergeant McIntrye was also taken into Cream’s confidence and shown a letter that had allegedly been received by the Stamford Street victimsof the Lambeth Poisoner, warning them about a Dr Harper, who would serve them as he had served Matilda Clover and a certain Louise Harvey

It was a fatal error. Dr Cream had indeed given Louise Harvey some pills to take the previous October. But she had only pretended to take them. She was very much alive, and willing to assist the police enquiries.

She told police how, on 25th or 26th October, she had met Cream in Regent Street about 12:30 at night, having seen him earlier that evening in the Alhambra Theatre at the back of the dress circle. She spent the night with him in a Soho hotel and met him again the following night on the Embankment, opposite Charing Cross underground station. ‘Good evening. ‘I’m late! ‘He said, giving her some roses and inviting her to take a glass of wine with him in a nearby pub, the Northumberland he produced some pill which he said would affect a cure. They were walking along the Embankment. Something in his manner put her on her guard. He insisted she took the pills and she pretended to swallow them, putting her hand to her mouth but when he looked away she threw them into the River. The solicitous doctor then bade her farewell. But before he left he gave her five shillings to go to a music-hall.

Oddly enough she saw him again about three weeks later, in Piccadilly Circus. He failed to recognise her, and when she approached him he invited her to a bar in Air Street, to join him for a glass of wine. ‘Don’t you know me? Don’t you remember me?’ she asked. ‘You promised to meet me one night outside the Oxford.’ ‘I don’t remember you. Who are you? ‘Have you forgotten Lou Harvey?’ she asked. He hurried away.

As described by Lou Harvey, Dr Cream was a ‘bald and very hairy man; he had a dark ginger moustache, wore gold rimmed glasses, was well-dressed, cross-eyed, and spoke with an odd accent.’

In fact, Thomas Neill Cream was Scottish, having been born in Glasgow on 27th May 1850, although he and his parents immigrated to Canada when he was thirteen. His father was the prosperous manager of a ship-building and lumber firm. Young Cream graduated as a doctor at McGill University, Montreal, in 1876. But thereafter he led an obsessional life of crime that included arson, abortion, blackmail, fraud, extortion, theft and attempted murder – each crime being followed up by a demand for some kind of payment. Three women died under his care as a doctor. A fourth, whom he had tried to abort, he was forced by her father to marry. She died of consumption when he was completing his medical studies in Edinburgh, where he was a qualified as a physician and surgeon. While practicing as a doctor of the ‘quack’ variety in Chicago he had an affair with a young woman, Miss Julia Scott, and poisoned her elderly and epileptic husband – who was taking Dr Cream’s medicinal cures, and whose life Dr Cream had thoughtfully tried to insure. Daniel Scott died on 14th July 1881 after imbibing on of Creams remedies, given to him by his wife. Before absconding with Mrs Scott, Cream wrote to the coroner and the District Attorney accusing a Chemist of malpractice and implying that Mr Scott had not died of natural causes and should be exhumed. He was, and was found to have been poisoned with strychnine.

The couple were apprehended and Mrs Scott turned stated evidence. Cream was sentenced to life imprisonment in Joliet prison, Illinois. He was released, unexpectedly early in July 1891. In the meantime his father had passed away, leaving him the healthy sum of $116,000.

Cream left America and by 1st October 1891, the month in which Ellen Donworth and Matilda Clover died and Louise Harvey escaped death, he had arrived in England.

By December he was engaged to Miss Sabbatini. In January, he returned to America and also visited Canada, where in Quebec, he had 500 leaflets printed (but never distributed) stating that one of the employees at the Metropole Hotel in London had poisoned Ellen Donworth. Then on the 9th April he made his way back to London; Emma Shrivell and Alice Marsh died three days later.

After Creams conversation with Sergeant McIntyre, the police began a very cautious investigation. Louis Harvey was tracked down and interviewed. Creams’ lodgings were watched, and he found himself shadowed. He told an acquaintance who pointed this out to him that the police were keeping an eye on young Harper. On 17th May another woman escaped poisoning when, in her room off Kennington Road, she wisely refused ‘an American drink” which Cream prepared for her. On the 26th May Inspector Tunbridge of the CID called on Cream in his rooms in Lambeth Palace Road. Cream complained about being followed by the police and showed Tunbridge a leather case containing, among other drug, a bottle of strychnine pills, which he said could only be sold to chemists or doctors. The following day, Tunbridge went to Barnstable and saw Doctor Harper, who showed him the threatening letter which was clearly written in Creams handwriting. But it was not until the 3rd June that Cream was arrested at his lodgings, having just booked passage to America.

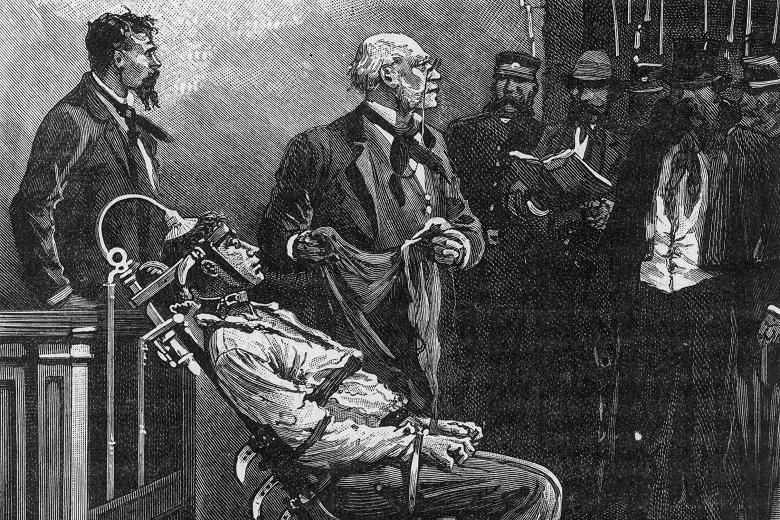

He was first charged with attempting to extort money from Doctor Joseph Harper. The inquest on Matilda Clover, who had been exhumed on 5th May, began on 22nd June. Its conclusion was that Thomas Neill, as he was still being called, had administered a poison with the intent to destroy life. Now charged with her murder, he was put on trial at the Old Bailey before Mr Justice Hawkins on 17th October 1892. The Attorney-General, Sir Charles Russell, led for the Crown, and Mr. Gerald Geoghegan appeared for the accused. Insolent and overbearing in court, Cream was convinced he would be acquitted. But the evidence was conclusive. After the sentence of death was pronounced, he muttered; “they will never hang me.”

The night before the execution Cream spent a sleepless night pacing his cell, reportedly shaking and as white as a sheet, despite his defiance he was hanged at Newgate prison 15th November 1892 at the age of 42. Madame Tussaud’s purchased his clothes and belongings for £200.

Meanwhile he continued to write: essays, poetry and plays. One of his comedies, Similia, had four hundred

consecutive performances in London before touring England. It made him a fortune, which he quickly scattered among his friends.

By the beginning of 1923, he was one of the "kings of London society".

Then, in September of that year, he vanished. He sold all his possessions, and gave his publisher carte blanche to handle his work. But before the end of the year he

reappeared in Dresden. The theatre then presented Similia with enormous success, the author himself translating it from English into German.

It went on to appear in many theatres along the Rhine. He founded a press for publishing modern poetry, and works on modern painting — Dorian Verlag —

whose editions are now worth a fortune.

But he was still something of a man of mystery. Every morning he galloped along the banks of the river Elbe until

nine o'clock; at ten he went to his office, eating lunch there.

At six in the evening, he went to art exhibitions or literary salons, and met friends. At nine, he returned home and no

one knew what he did for the rest of the evening. And no one liked to ask him.

One reason for this regular life was that he was in love - the girl was called Wally von Hammerstein, daughter of

aristocratic parents, who were favourably impressed with the young writer. Their engagement was to be announced on 4 October 1924.

But on the previous day Whitecliffe disappeared again. He failed to arrive at his office, and vanished from his flat. The frantic Wally searched Dresden, without success. The police were alerted

- discreetly - and persued diligent inquiries. Thier theroy was that he had committed suicide. Wally believed that he had either met with an accident or had become the victim of crime -

he often carried large sums of money. As the weeks went by her desperation turned to misery; she talked about joining a convent.

Meanwhile he continued to write: essays, poetry and plays. One of his comedies, Similia, had four hundred

consecutive performances in London before touring England. It made him a fortune, which he quickly scattered among his friends.

By the beginning of 1923, he was one of the "kings of London society".

Then, in September of that year, he vanished. He sold all his possessions, and gave his publisher carte blanche to handle his work. But before the end of the year he

reappeared in Dresden. The theatre then presented Similia with enormous success, the author himself translating it from English into German.

It went on to appear in many theatres along the Rhine. He founded a press for publishing modern poetry, and works on modern painting — Dorian Verlag —

whose editions are now worth a fortune.

But he was still something of a man of mystery. Every morning he galloped along the banks of the river Elbe until

nine o'clock; at ten he went to his office, eating lunch there.

At six in the evening, he went to art exhibitions or literary salons, and met friends. At nine, he returned home and no

one knew what he did for the rest of the evening. And no one liked to ask him.

One reason for this regular life was that he was in love - the girl was called Wally von Hammerstein, daughter of

aristocratic parents, who were favourably impressed with the young writer. Their engagement was to be announced on 4 October 1924.

But on the previous day Whitecliffe disappeared again. He failed to arrive at his office, and vanished from his flat. The frantic Wally searched Dresden, without success. The police were alerted

- discreetly - and persued diligent inquiries. Thier theroy was that he had committed suicide. Wally believed that he had either met with an accident or had become the victim of crime -

he often carried large sums of money. As the weeks went by her desperation turned to misery; she talked about joining a convent.

Then she received a letter. It had been found in the cell of a condemned man who had committed suicide in Berlin he had succeeded in opening his veins with

the buckle of his belt. The inscription on the envelope said: "I beg you, monsieur le procureur of the Reich, to forward this letter to its destination

without opening it." It was signed: Lovach Blume.

Blume was apparently one of the most horrible of murderers, worse than Jack the Ripper or Peter Kurten, the Düsseldorf sadist. He had admitted to the court that

tried him: "Every ten days I have to kill. I am driven by an irresistible urge, so that until I have killed, I suffer atrociously.

But as I disembowel my victims I feel an indescribable pleasure." Asked about his past, he declared: "I am a

corpse. Why bother about the past of a corpse?" Blume's victims were prostitutes and homeless girls picked up on the Berlin streets. He would take them to a

hotel, and kill them as soon as they were undressed. Then, with a knife like a Malaysian "kris", with an ivory handle, he

would perform horrible mutilations, so awful that even doctors found the sight unbearable. These murders continued over a period of six months, during which the slum

quarters of Berlin lived in fear.

Blume was finally arrested by accident, in September 1924. The police thought he was engaged in drug trafficking-

and knocked on the door of a hotel room minutes after Blume had entered with a prostitute. Blume had just

commited his thirty -first murder in Berlin; he was standing naked by the window, and the woman's body lay at his feet.

He made no resistance, and admitted freely to his crimes he could only recall twenty-seven. He declared that he

had no fear of death — particularly the way executions were performed in Germany (by decapitation), which he greatly

preferred to the English custom of hanging.

This was the man who had committed suicide in his prison cell, and who addressed a long letter to his fiancee,

Wally von Hammerstein. He told her that he was certain the devil existed, because he had met him. He was, he

explained, a kind of Jekyll-and-Hyde, an intelligent, talented man who suddenly became cruel and bloodthirsty.

He thought of himself as being like victims of demoniacal possession. He had left London after committing nine

murders, when he suspected that Scotland Yard was on his trail. His love for Wally was genuine, he told her, and

had caused him to "die a little". He had hoped once that she might be able to save him from his demons, but it had proved a vain hope.

Wally fainted as she read the letter. And in 1925 she entered a nunnery and took the name Marie de Douleurs.

There she prays for the salvation of a tortured soul. . . .

This is the story, as told by Louis Pauwels — a writer who became famous for his collaboration with Jacques Bergier

on a book called The Morning of the Magicians. Critics pointed out that that book was full of factual errors, and a

number of these can also be found in his article on Whitecliffe. For example, if the date of Blume's arrest is

correct — 25 September 1924 — then it took place before Whitecliffe vanished from Dresden, on 3 October 1924 . . .But this, presumably, is a slip of the pen.

But who was Harry Whitecliffe? According to Pauwels, he told the Berlin court that his father was German, his

mother Danish, and that he was brought up in Australia by an uncle who was a butcher. His uncle lived in Sydney.

But in a "conversation" between Pauwels and his fellow author at the end of one chapter, Pauwels states that Whitecliffe was the son

of a great English family. But apart from the three magistrates who opened the suicide letter — ignoring Blume's last wishes — only Wally and her parents knew

Whitecliffe's true identity. The judges are dead, so are Wally's parents. Wally never told anyone of this drama of her youth.

We are left to assume that she told the story to Pauwels.

This extraordinary tale aroused the curiosity of a well-known French authoress, Francoise d"Eaubonne, who felt

that Whitecliffe deserved a book to himself. But her letters to the two authors — Pauwels and Breton — went unanswered. She therefore contacted the British Society of

Theatre Research, and so entered into a correspondence with the theatre historian John Kennedy Melling. Melling had never heard of Whitecliffe, or of a play called Similia.

He decided to begin his researches by contacting Scotland Yard, to ask whether they have any record of an unknown sex killer of the early 1920s.

Their reply was negative; there was no series of Ripper-type murders of prostitutes in the

early 1920s. He next applied to J. H. H. Gaute, the possessor of the largest crime library in the British Isles; Gaute could also find no trace of such a

series of sex crimes in the 1920s. Theatrical reference books contained no mention of Harry Whitecliffe, or of his successful comedy

Similia. It began to look — as incredible as it sounds — as if Pauwels had simply invented the whole story.

Thelma Holland, Oscar Wilde's daughter-in-law, could find no trace of a volume of parodies of Wilde among the comprehensive collection of her late husband, Vyvyan

]Holland. But she had a suggestion to make - to address inquiries to the Mitchell Library in Sydney. As an Australian, she felt it was probably Melling's best chance of

tracking down Harry Whitecliffe.

Then she received a letter. It had been found in the cell of a condemned man who had committed suicide in Berlin he had succeeded in opening his veins with

the buckle of his belt. The inscription on the envelope said: "I beg you, monsieur le procureur of the Reich, to forward this letter to its destination

without opening it." It was signed: Lovach Blume.

Blume was apparently one of the most horrible of murderers, worse than Jack the Ripper or Peter Kurten, the Düsseldorf sadist. He had admitted to the court that

tried him: "Every ten days I have to kill. I am driven by an irresistible urge, so that until I have killed, I suffer atrociously.

But as I disembowel my victims I feel an indescribable pleasure." Asked about his past, he declared: "I am a

corpse. Why bother about the past of a corpse?" Blume's victims were prostitutes and homeless girls picked up on the Berlin streets. He would take them to a

hotel, and kill them as soon as they were undressed. Then, with a knife like a Malaysian "kris", with an ivory handle, he

would perform horrible mutilations, so awful that even doctors found the sight unbearable. These murders continued over a period of six months, during which the slum

quarters of Berlin lived in fear.

Blume was finally arrested by accident, in September 1924. The police thought he was engaged in drug trafficking-

and knocked on the door of a hotel room minutes after Blume had entered with a prostitute. Blume had just

commited his thirty -first murder in Berlin; he was standing naked by the window, and the woman's body lay at his feet.

He made no resistance, and admitted freely to his crimes he could only recall twenty-seven. He declared that he

had no fear of death — particularly the way executions were performed in Germany (by decapitation), which he greatly

preferred to the English custom of hanging.

This was the man who had committed suicide in his prison cell, and who addressed a long letter to his fiancee,

Wally von Hammerstein. He told her that he was certain the devil existed, because he had met him. He was, he

explained, a kind of Jekyll-and-Hyde, an intelligent, talented man who suddenly became cruel and bloodthirsty.

He thought of himself as being like victims of demoniacal possession. He had left London after committing nine

murders, when he suspected that Scotland Yard was on his trail. His love for Wally was genuine, he told her, and

had caused him to "die a little". He had hoped once that she might be able to save him from his demons, but it had proved a vain hope.

Wally fainted as she read the letter. And in 1925 she entered a nunnery and took the name Marie de Douleurs.

There she prays for the salvation of a tortured soul. . . .

This is the story, as told by Louis Pauwels — a writer who became famous for his collaboration with Jacques Bergier

on a book called The Morning of the Magicians. Critics pointed out that that book was full of factual errors, and a

number of these can also be found in his article on Whitecliffe. For example, if the date of Blume's arrest is

correct — 25 September 1924 — then it took place before Whitecliffe vanished from Dresden, on 3 October 1924 . . .But this, presumably, is a slip of the pen.

But who was Harry Whitecliffe? According to Pauwels, he told the Berlin court that his father was German, his

mother Danish, and that he was brought up in Australia by an uncle who was a butcher. His uncle lived in Sydney.

But in a "conversation" between Pauwels and his fellow author at the end of one chapter, Pauwels states that Whitecliffe was the son

of a great English family. But apart from the three magistrates who opened the suicide letter — ignoring Blume's last wishes — only Wally and her parents knew

Whitecliffe's true identity. The judges are dead, so are Wally's parents. Wally never told anyone of this drama of her youth.

We are left to assume that she told the story to Pauwels.

This extraordinary tale aroused the curiosity of a well-known French authoress, Francoise d"Eaubonne, who felt

that Whitecliffe deserved a book to himself. But her letters to the two authors — Pauwels and Breton — went unanswered. She therefore contacted the British Society of

Theatre Research, and so entered into a correspondence with the theatre historian John Kennedy Melling. Melling had never heard of Whitecliffe, or of a play called Similia.

He decided to begin his researches by contacting Scotland Yard, to ask whether they have any record of an unknown sex killer of the early 1920s.

Their reply was negative; there was no series of Ripper-type murders of prostitutes in the

early 1920s. He next applied to J. H. H. Gaute, the possessor of the largest crime library in the British Isles; Gaute could also find no trace of such a

series of sex crimes in the 1920s. Theatrical reference books contained no mention of Harry Whitecliffe, or of his successful comedy

Similia. It began to look — as incredible as it sounds — as if Pauwels had simply invented the whole story.

Thelma Holland, Oscar Wilde's daughter-in-law, could find no trace of a volume of parodies of Wilde among the comprehensive collection of her late husband, Vyvyan

]Holland. But she had a suggestion to make - to address inquiries to the Mitchell Library in Sydney. As an Australian, she felt it was probably Melling's best chance of

tracking down Harry Whitecliffe.

Incredibly, this long shot brought positive results: not about Harry Whitecliffe, but about a German murderer called Blume — not Lovach, but Wilhelm Blume. The Argus

newspaper for 8 August 1922 contained a story headed "Cultured Murderer", and sub-titled: "Literary Man's Series of Crimes". It was datelined Berlin, 7 August.

Wilhelm Blume, a man of wide culture and considerable literary gifts, whose translations of English plays have been produced in Dresden with great

success, has confessed to a series of cold-blooded murders, one of which was perpetrated at the Hotel Adlon, the best known Berlin hotel.

The most significant item in the newspaper report is that Blume had founded a publishing house called Dorian Press (Verlag) in Dresden.

This is obviously the same Blume who — according to Pauwels — committed suicide in Berlin.

Incredibly, this long shot brought positive results: not about Harry Whitecliffe, but about a German murderer called Blume — not Lovach, but Wilhelm Blume. The Argus

newspaper for 8 August 1922 contained a story headed "Cultured Murderer", and sub-titled: "Literary Man's Series of Crimes". It was datelined Berlin, 7 August.

Wilhelm Blume, a man of wide culture and considerable literary gifts, whose translations of English plays have been produced in Dresden with great

success, has confessed to a series of cold-blooded murders, one of which was perpetrated at the Hotel Adlon, the best known Berlin hotel.

The most significant item in the newspaper report is that Blume had founded a publishing house called Dorian Press (Verlag) in Dresden.

This is obviously the same Blume who — according to Pauwels — committed suicide in Berlin.

But Wilhelm Blume was not a sex killer. His victims had been postmen, and the motive had been robbery. In Germany postal orders were paid to consignees in their

own homes, so postmen often carried fairly large sums of money. Blume had sent himself postal orders, then killed the

postmen and robbed them — the exact number is not stated in the Argus article. The first time he did this he was interrupted by his landlady while he was

strangling the postman with a noose; and he cut her throat. Then he moved on to Dresden, where in due course he attempted to rob another postman.

Armed with two revolvers, he. waited for the postman in the porch of a house. But the tenant of the house arrived so promptly that he had to flee, shooting

one of the policemen. Then his revolvers both misfired, and he was caught. Apparently he attempted to commit suicide in prison, but failed.

He confessed — as the Argus states — to several murders, and was presumably executed later in 1922 (although the Argus carries no further record).

It seems plain, then, that the question"Who was Harry Whitecliffe?" should be re-worded "Who was Wihlem Blume?" For Blume and Whitecliffe were obviuosly the same person.

From the information we possess, we can a tentative reconstruction of the story of Blumea—Whitecliffe. He sounds like a typical example of a certain type of killer

who is also a confidence man — other examples are Landru, Petiot, the "acid bath murderer" Haigh, and the sex

killer Neville Heath. It is an essential part of such a man's personality that he is a fantasist, and that he likes to pose as

a success, and to talk casually about past triumphs. (Neville Heath called himself "Group Captain Rupert Brooke".)

They usually start off as petty swindlers, then gradually become more ambitious and graduate to murder. This is what Blume seems to have done. In the chaos of postwar

Berlin he made a quick fortune by murdering and robbing postmen. Perhaps his last coup made him a fortune beyond his expectations, or perhaps the Berlin postal authorities

were now on the alert for the killer. Blume decided it was time to make an attempt to live a respectable life, and to put his literary fantasies into operation.

He moved to Dresden, calling himself Harry Whitecliffe, and set up Dorian Verlag. He became a successful translator of English plays, and may

have helped to finance their production in Dresden and in theatres along the Rhine. Since he was posing as an upper class Englishman,

and must have occasionally run into other Englishmen in Dresden, we may assume that his English was perfect, and that his story of being brought up in

Australia was probably true. Since he also spoke perfect German, it is also a fair assumption that he was, as he told the court, the son of a German father

and a Danish mother. He fell in love with an upper class girl, and told her a romantic story that is typical of the inveterate daydreamer:

that he was the son of a "great English family", that he had become an overnight literary success in London as a result of his pastiches of Oscar Wilde,

but had at first preferred to shun the limelight (this is the true Walter Mitty touch) until increasing success made this impossible. His wealth is the

result of a successful play, Similia. (The similarity of the title to Salome is obvious, and we may infer that Blume was an ardent admirer of Wilde.)

But in order to avoid too much publicity — after all, victims of previous swindles might expose him — he lives the quiet, regular life of a crook in hiding.

And just as all seems to be going so well — just as success, respectability, a happy marriage, seem so close — he once again runs out of money.

There is only one solution: a brief return to a life of crime. One or two robberies of postmen can replenish his bank account and secure his future . . . But

this time it goes disastrously wrong. Harry Whitecliffe is exposed as the swindler and murderer Wilhelm Blume. He makes no attempt to deny it, and

confesses to his previous murders; his world has now collapsed in ruins. He is sent back to Berlin, where the murders were committed, and he attempts suicide

in his cell. Soon after, he dies by the guillotine. And in Dresden the true story of Wilhelm Blume is soon embroidered into a horrifying tale of a Jekyll-and-

Hyde mass murderer, whose early career in London is confused with Jack the Ripper... .

Do any records of Wilhelm Blume still exist? It seems doubtful — the fire-bombing of Dresden destroyed most of

the civic records, and the people who knew him more than sixty years ago must now all be dead. Yet Pauwels has

obviously come across some garbled and wildly inaccurate account of Blume's career as Harry Whitecliffe. It would be

interesting to know where he obtained his information; but neither Francoise d"Eaubonne nor John Kennedy Melling

have been successful in persuading him to answer letters.

But Wilhelm Blume was not a sex killer. His victims had been postmen, and the motive had been robbery. In Germany postal orders were paid to consignees in their

own homes, so postmen often carried fairly large sums of money. Blume had sent himself postal orders, then killed the

postmen and robbed them — the exact number is not stated in the Argus article. The first time he did this he was interrupted by his landlady while he was

strangling the postman with a noose; and he cut her throat. Then he moved on to Dresden, where in due course he attempted to rob another postman.

Armed with two revolvers, he. waited for the postman in the porch of a house. But the tenant of the house arrived so promptly that he had to flee, shooting

one of the policemen. Then his revolvers both misfired, and he was caught. Apparently he attempted to commit suicide in prison, but failed.

He confessed — as the Argus states — to several murders, and was presumably executed later in 1922 (although the Argus carries no further record).

It seems plain, then, that the question"Who was Harry Whitecliffe?" should be re-worded "Who was Wihlem Blume?" For Blume and Whitecliffe were obviuosly the same person.

From the information we possess, we can a tentative reconstruction of the story of Blumea—Whitecliffe. He sounds like a typical example of a certain type of killer

who is also a confidence man — other examples are Landru, Petiot, the "acid bath murderer" Haigh, and the sex

killer Neville Heath. It is an essential part of such a man's personality that he is a fantasist, and that he likes to pose as

a success, and to talk casually about past triumphs. (Neville Heath called himself "Group Captain Rupert Brooke".)

They usually start off as petty swindlers, then gradually become more ambitious and graduate to murder. This is what Blume seems to have done. In the chaos of postwar

Berlin he made a quick fortune by murdering and robbing postmen. Perhaps his last coup made him a fortune beyond his expectations, or perhaps the Berlin postal authorities

were now on the alert for the killer. Blume decided it was time to make an attempt to live a respectable life, and to put his literary fantasies into operation.

He moved to Dresden, calling himself Harry Whitecliffe, and set up Dorian Verlag. He became a successful translator of English plays, and may

have helped to finance their production in Dresden and in theatres along the Rhine. Since he was posing as an upper class Englishman,

and must have occasionally run into other Englishmen in Dresden, we may assume that his English was perfect, and that his story of being brought up in

Australia was probably true. Since he also spoke perfect German, it is also a fair assumption that he was, as he told the court, the son of a German father

and a Danish mother. He fell in love with an upper class girl, and told her a romantic story that is typical of the inveterate daydreamer:

that he was the son of a "great English family", that he had become an overnight literary success in London as a result of his pastiches of Oscar Wilde,

but had at first preferred to shun the limelight (this is the true Walter Mitty touch) until increasing success made this impossible. His wealth is the

result of a successful play, Similia. (The similarity of the title to Salome is obvious, and we may infer that Blume was an ardent admirer of Wilde.)

But in order to avoid too much publicity — after all, victims of previous swindles might expose him — he lives the quiet, regular life of a crook in hiding.

And just as all seems to be going so well — just as success, respectability, a happy marriage, seem so close — he once again runs out of money.

There is only one solution: a brief return to a life of crime. One or two robberies of postmen can replenish his bank account and secure his future . . . But

this time it goes disastrously wrong. Harry Whitecliffe is exposed as the swindler and murderer Wilhelm Blume. He makes no attempt to deny it, and

confesses to his previous murders; his world has now collapsed in ruins. He is sent back to Berlin, where the murders were committed, and he attempts suicide

in his cell. Soon after, he dies by the guillotine. And in Dresden the true story of Wilhelm Blume is soon embroidered into a horrifying tale of a Jekyll-and-

Hyde mass murderer, whose early career in London is confused with Jack the Ripper... .

Do any records of Wilhelm Blume still exist? It seems doubtful — the fire-bombing of Dresden destroyed most of

the civic records, and the people who knew him more than sixty years ago must now all be dead. Yet Pauwels has

obviously come across some garbled and wildly inaccurate account of Blume's career as Harry Whitecliffe. It would be

interesting to know where he obtained his information; but neither Francoise d"Eaubonne nor John Kennedy Melling

have been successful in persuading him to answer letters.

Then the poisoner’s epistles and murderous activities suddenly ceased. He had fallen in love and had become engaged.

Several months later, on the 12th April 1892, two more young prostitutes died in agony. They were Emma Shrivell and Alice Marsh, who both lived in second-floor rooms in 118 Stamford Street, a house of ill-fame kept by a woman called Vogt. Before they died the girls told a policeman that a doctor called Fred had visited them that night, and after a meal of bottled beer and tinned salmon he had given each of them three long thin pills. He was stoutish, dark, bald on top of his head, wore glasses, and was about 5ft 8 ins or 9ins. The policeman, PC Cumley, recalled seeing such a man leave the building at 01:45am.

It was established later both prostitutes had been poisoned with strychnine, and the newspapers speculated wildly about the identity of the Lambeth Poisoner. Could he be Jack the Ripper, whose identity had suddenly ceased in 1888?

Then the poisoner’s epistles and murderous activities suddenly ceased. He had fallen in love and had become engaged.

Several months later, on the 12th April 1892, two more young prostitutes died in agony. They were Emma Shrivell and Alice Marsh, who both lived in second-floor rooms in 118 Stamford Street, a house of ill-fame kept by a woman called Vogt. Before they died the girls told a policeman that a doctor called Fred had visited them that night, and after a meal of bottled beer and tinned salmon he had given each of them three long thin pills. He was stoutish, dark, bald on top of his head, wore glasses, and was about 5ft 8 ins or 9ins. The policeman, PC Cumley, recalled seeing such a man leave the building at 01:45am.

It was established later both prostitutes had been poisoned with strychnine, and the newspapers speculated wildly about the identity of the Lambeth Poisoner. Could he be Jack the Ripper, whose identity had suddenly ceased in 1888?

‘What a cold-blooded murder!’ exclaimed Dr Neill (Thomas Neill Cream called himself) when he read about the inquest on the two girls in a newspaper on Easter Sunday on the 17th April. He told his landlady’s daughter, Miss Sleaper, that he was determined to bring the miscreant to justice. A tall, bald, cross-eyed, broad-shouldered man who wore tall hats and glasses specially made for him in Fleet Street, Dr Cream had rented a second-floor room in 108 Lambeth Place Road since 9th April, after returning to London from Canada. He had stayed there before, between 07th October the previous year and January, when he took a trip to America. In December, he had become engaged to a girl called Laura Sabbtini, who lived with her mother in Berkhamsted. He made out a will in her favour. On Christmas Day he had dined with the Sleapers in his lodgings, joined in their family entertainments, singing hymns in the evening and playing the zither. He was no trouble, going out at night alone to places of entertainment and debauchery.

In those days that area south of the River Thames between Westminster and Waterloo bridges was thronged with pubs, theatres, prostitutes and other amusements. There was Astley’s circus and playhouse; the surrey, with its rowdy melodramas (gallery, 6d; pit 1s); the Canterbury music-hall, with its picture gallery; and the Old Vic, which had, however, become respectable, with blameless programmes and temperance bars, since Emma Cons became a director in 1880.

Cream was ready on his night-time jaunts, it seems, to converse with any man about plays or music, but his favourite topic was women, about who he spoke crudely. He would describe his tastes and pleasures and exhibit a collection of indecent pictures which he carried about him.

An article published in the St James Gazette said he dressed with taste and care and was well-informed. It continued: ‘His very strong and protruding under-jaw was always at work chewing gum, tobacco or cigars…He never laughed or even smiled…He occasionally said “Ha-ha!” in a hard, stage-villain-like fashion, but no amount of good nature could construe it into an expression of geniality.’ The article also referred to his ‘never-ending talk about women’ and referred to the fact that he swallowed pills which he said had aphrodisiac properties.

In the same lodging house as Dr Cream was a young medical student from St Thomas’s Hospital, Walter Harper. Cream told Miss Sleaper most forcibly that it was Harper who had killed the girls. The police had proof, he said, and the girls had been warned by letter. Miss Sleaper, a girl of spirit, replied that he must be mad. Unabashed, Cream wrote to young Harper’s father, a doctor in Barnstable, accusing his son of the murders and offered to exchange such evidence as he had for £1,500. He wrote; ‘The publication of the evidence will ruin you and your family forever, so that when you read it you will tell no one to tell you that it will convict your son…if you do not answer me at once, I am going to give evidence to the coroner at once.’

Cream was just as outspoken with a drinking acquaintance, an engineer named Haynes, who also happened to be a private enquiry agent. Haynes showed great interests in what Cream had to say, and in due course disclosed all he had discovered to Police Sergeant McItyre of the CID. Sergeant McIntrye was also taken into Cream’s confidence and shown a letter that had allegedly been received by the Stamford Street victimsof the Lambeth Poisoner, warning them about a Dr Harper, who would serve them as he had served Matilda Clover and a certain Louise Harvey

It was a fatal error. Dr Cream had indeed given Louise Harvey some pills to take the previous October. But she had only pretended to take them. She was very much alive, and willing to assist the police enquiries.

‘What a cold-blooded murder!’ exclaimed Dr Neill (Thomas Neill Cream called himself) when he read about the inquest on the two girls in a newspaper on Easter Sunday on the 17th April. He told his landlady’s daughter, Miss Sleaper, that he was determined to bring the miscreant to justice. A tall, bald, cross-eyed, broad-shouldered man who wore tall hats and glasses specially made for him in Fleet Street, Dr Cream had rented a second-floor room in 108 Lambeth Place Road since 9th April, after returning to London from Canada. He had stayed there before, between 07th October the previous year and January, when he took a trip to America. In December, he had become engaged to a girl called Laura Sabbtini, who lived with her mother in Berkhamsted. He made out a will in her favour. On Christmas Day he had dined with the Sleapers in his lodgings, joined in their family entertainments, singing hymns in the evening and playing the zither. He was no trouble, going out at night alone to places of entertainment and debauchery.

In those days that area south of the River Thames between Westminster and Waterloo bridges was thronged with pubs, theatres, prostitutes and other amusements. There was Astley’s circus and playhouse; the surrey, with its rowdy melodramas (gallery, 6d; pit 1s); the Canterbury music-hall, with its picture gallery; and the Old Vic, which had, however, become respectable, with blameless programmes and temperance bars, since Emma Cons became a director in 1880.

Cream was ready on his night-time jaunts, it seems, to converse with any man about plays or music, but his favourite topic was women, about who he spoke crudely. He would describe his tastes and pleasures and exhibit a collection of indecent pictures which he carried about him.

An article published in the St James Gazette said he dressed with taste and care and was well-informed. It continued: ‘His very strong and protruding under-jaw was always at work chewing gum, tobacco or cigars…He never laughed or even smiled…He occasionally said “Ha-ha!” in a hard, stage-villain-like fashion, but no amount of good nature could construe it into an expression of geniality.’ The article also referred to his ‘never-ending talk about women’ and referred to the fact that he swallowed pills which he said had aphrodisiac properties.

In the same lodging house as Dr Cream was a young medical student from St Thomas’s Hospital, Walter Harper. Cream told Miss Sleaper most forcibly that it was Harper who had killed the girls. The police had proof, he said, and the girls had been warned by letter. Miss Sleaper, a girl of spirit, replied that he must be mad. Unabashed, Cream wrote to young Harper’s father, a doctor in Barnstable, accusing his son of the murders and offered to exchange such evidence as he had for £1,500. He wrote; ‘The publication of the evidence will ruin you and your family forever, so that when you read it you will tell no one to tell you that it will convict your son…if you do not answer me at once, I am going to give evidence to the coroner at once.’

Cream was just as outspoken with a drinking acquaintance, an engineer named Haynes, who also happened to be a private enquiry agent. Haynes showed great interests in what Cream had to say, and in due course disclosed all he had discovered to Police Sergeant McItyre of the CID. Sergeant McIntrye was also taken into Cream’s confidence and shown a letter that had allegedly been received by the Stamford Street victimsof the Lambeth Poisoner, warning them about a Dr Harper, who would serve them as he had served Matilda Clover and a certain Louise Harvey

It was a fatal error. Dr Cream had indeed given Louise Harvey some pills to take the previous October. But she had only pretended to take them. She was very much alive, and willing to assist the police enquiries.  Oddly enough she saw him again about three weeks later, in Piccadilly Circus. He failed to recognise her, and when she approached him he invited her to a bar in Air Street, to join him for a glass of wine. ‘Don’t you know me? Don’t you remember me?’ she asked. ‘You promised to meet me one night outside the Oxford.’ ‘I don’t remember you. Who are you? ‘Have you forgotten Lou Harvey?’ she asked. He hurried away.

As described by Lou Harvey, Dr Cream was a ‘bald and very hairy man; he had a dark ginger moustache, wore gold rimmed glasses, was well-dressed, cross-eyed, and spoke with an odd accent.’

In fact, Thomas Neill Cream was Scottish, having been born in Glasgow on 27th May 1850, although he and his parents immigrated to Canada when he was thirteen. His father was the prosperous manager of a ship-building and lumber firm. Young Cream graduated as a doctor at McGill University, Montreal, in 1876. But thereafter he led an obsessional life of crime that included arson, abortion, blackmail, fraud, extortion, theft and attempted murder – each crime being followed up by a demand for some kind of payment. Three women died under his care as a doctor. A fourth, whom he had tried to abort, he was forced by her father to marry. She died of consumption when he was completing his medical studies in Edinburgh, where he was a qualified as a physician and surgeon. While practicing as a doctor of the ‘quack’ variety in Chicago he had an affair with a young woman, Miss Julia Scott, and poisoned her elderly and epileptic husband – who was taking Dr Cream’s medicinal cures, and whose life Dr Cream had thoughtfully tried to insure. Daniel Scott died on 14th July 1881 after imbibing on of Creams remedies, given to him by his wife. Before absconding with Mrs Scott, Cream wrote to the coroner and the District Attorney accusing a Chemist of malpractice and implying that Mr Scott had not died of natural causes and should be exhumed. He was, and was found to have been poisoned with strychnine.

The couple were apprehended and Mrs Scott turned stated evidence. Cream was sentenced to life imprisonment in Joliet prison, Illinois. He was released, unexpectedly early in July 1891. In the meantime his father had passed away, leaving him the healthy sum of $116,000.

Oddly enough she saw him again about three weeks later, in Piccadilly Circus. He failed to recognise her, and when she approached him he invited her to a bar in Air Street, to join him for a glass of wine. ‘Don’t you know me? Don’t you remember me?’ she asked. ‘You promised to meet me one night outside the Oxford.’ ‘I don’t remember you. Who are you? ‘Have you forgotten Lou Harvey?’ she asked. He hurried away.

As described by Lou Harvey, Dr Cream was a ‘bald and very hairy man; he had a dark ginger moustache, wore gold rimmed glasses, was well-dressed, cross-eyed, and spoke with an odd accent.’

In fact, Thomas Neill Cream was Scottish, having been born in Glasgow on 27th May 1850, although he and his parents immigrated to Canada when he was thirteen. His father was the prosperous manager of a ship-building and lumber firm. Young Cream graduated as a doctor at McGill University, Montreal, in 1876. But thereafter he led an obsessional life of crime that included arson, abortion, blackmail, fraud, extortion, theft and attempted murder – each crime being followed up by a demand for some kind of payment. Three women died under his care as a doctor. A fourth, whom he had tried to abort, he was forced by her father to marry. She died of consumption when he was completing his medical studies in Edinburgh, where he was a qualified as a physician and surgeon. While practicing as a doctor of the ‘quack’ variety in Chicago he had an affair with a young woman, Miss Julia Scott, and poisoned her elderly and epileptic husband – who was taking Dr Cream’s medicinal cures, and whose life Dr Cream had thoughtfully tried to insure. Daniel Scott died on 14th July 1881 after imbibing on of Creams remedies, given to him by his wife. Before absconding with Mrs Scott, Cream wrote to the coroner and the District Attorney accusing a Chemist of malpractice and implying that Mr Scott had not died of natural causes and should be exhumed. He was, and was found to have been poisoned with strychnine.

The couple were apprehended and Mrs Scott turned stated evidence. Cream was sentenced to life imprisonment in Joliet prison, Illinois. He was released, unexpectedly early in July 1891. In the meantime his father had passed away, leaving him the healthy sum of $116,000.

Cream left America and by 1st October 1891, the month in which Ellen Donworth and Matilda Clover died and Louise Harvey escaped death, he had arrived in England.

By December he was engaged to Miss Sabbatini. In January, he returned to America and also visited Canada, where in Quebec, he had 500 leaflets printed (but never distributed) stating that one of the employees at the Metropole Hotel in London had poisoned Ellen Donworth. Then on the 9th April he made his way back to London; Emma Shrivell and Alice Marsh died three days later.

After Creams conversation with Sergeant McIntyre, the police began a very cautious investigation. Louis Harvey was tracked down and interviewed. Creams’ lodgings were watched, and he found himself shadowed. He told an acquaintance who pointed this out to him that the police were keeping an eye on young Harper. On 17th May another woman escaped poisoning when, in her room off Kennington Road, she wisely refused ‘an American drink” which Cream prepared for her. On the 26th May Inspector Tunbridge of the CID called on Cream in his rooms in Lambeth Palace Road. Cream complained about being followed by the police and showed Tunbridge a leather case containing, among other drug, a bottle of strychnine pills, which he said could only be sold to chemists or doctors. The following day, Tunbridge went to Barnstable and saw Doctor Harper, who showed him the threatening letter which was clearly written in Creams handwriting. But it was not until the 3rd June that Cream was arrested at his lodgings, having just booked passage to America.

Cream left America and by 1st October 1891, the month in which Ellen Donworth and Matilda Clover died and Louise Harvey escaped death, he had arrived in England.

By December he was engaged to Miss Sabbatini. In January, he returned to America and also visited Canada, where in Quebec, he had 500 leaflets printed (but never distributed) stating that one of the employees at the Metropole Hotel in London had poisoned Ellen Donworth. Then on the 9th April he made his way back to London; Emma Shrivell and Alice Marsh died three days later.

After Creams conversation with Sergeant McIntyre, the police began a very cautious investigation. Louis Harvey was tracked down and interviewed. Creams’ lodgings were watched, and he found himself shadowed. He told an acquaintance who pointed this out to him that the police were keeping an eye on young Harper. On 17th May another woman escaped poisoning when, in her room off Kennington Road, she wisely refused ‘an American drink” which Cream prepared for her. On the 26th May Inspector Tunbridge of the CID called on Cream in his rooms in Lambeth Palace Road. Cream complained about being followed by the police and showed Tunbridge a leather case containing, among other drug, a bottle of strychnine pills, which he said could only be sold to chemists or doctors. The following day, Tunbridge went to Barnstable and saw Doctor Harper, who showed him the threatening letter which was clearly written in Creams handwriting. But it was not until the 3rd June that Cream was arrested at his lodgings, having just booked passage to America.

He was first charged with attempting to extort money from Doctor Joseph Harper. The inquest on Matilda Clover, who had been exhumed on 5th May, began on 22nd June. Its conclusion was that Thomas Neill, as he was still being called, had administered a poison with the intent to destroy life. Now charged with her murder, he was put on trial at the Old Bailey before Mr Justice Hawkins on 17th October 1892. The Attorney-General, Sir Charles Russell, led for the Crown, and Mr. Gerald Geoghegan appeared for the accused. Insolent and overbearing in court, Cream was convinced he would be acquitted. But the evidence was conclusive. After the sentence of death was pronounced, he muttered; “they will never hang me.”

The night before the execution Cream spent a sleepless night pacing his cell, reportedly shaking and as white as a sheet, despite his defiance he was hanged at Newgate prison 15th November 1892 at the age of 42. Madame Tussaud’s purchased his clothes and belongings for £200.

He was first charged with attempting to extort money from Doctor Joseph Harper. The inquest on Matilda Clover, who had been exhumed on 5th May, began on 22nd June. Its conclusion was that Thomas Neill, as he was still being called, had administered a poison with the intent to destroy life. Now charged with her murder, he was put on trial at the Old Bailey before Mr Justice Hawkins on 17th October 1892. The Attorney-General, Sir Charles Russell, led for the Crown, and Mr. Gerald Geoghegan appeared for the accused. Insolent and overbearing in court, Cream was convinced he would be acquitted. But the evidence was conclusive. After the sentence of death was pronounced, he muttered; “they will never hang me.”

The night before the execution Cream spent a sleepless night pacing his cell, reportedly shaking and as white as a sheet, despite his defiance he was hanged at Newgate prison 15th November 1892 at the age of 42. Madame Tussaud’s purchased his clothes and belongings for £200.

The evening of 19 January 1931 was chilly and damp, but by seven o’clock, a few members had already arrived at the chess club in the City Café. Shortly after 7.15, the telephone rang. Samuel Beattie, captain of the club answered it. A mans voice asked for Wallace. Beattie said that Wallace would be in later to play a match and suggested he call back later. “No, I’m too busy – I have my girls twenty-first birthday on.” The man said his name was Qualtrough, and asked if Beattie could give him a message. Beattie wrote it down. It asked Wallace to go to Qualtrough’s home as 25 Menlove Gardens East the following evening at 7:30. It was, said Qualthrough, a matter of business.

The evening of 19 January 1931 was chilly and damp, but by seven o’clock, a few members had already arrived at the chess club in the City Café. Shortly after 7.15, the telephone rang. Samuel Beattie, captain of the club answered it. A mans voice asked for Wallace. Beattie said that Wallace would be in later to play a match and suggested he call back later. “No, I’m too busy – I have my girls twenty-first birthday on.” The man said his name was Qualtrough, and asked if Beattie could give him a message. Beattie wrote it down. It asked Wallace to go to Qualtrough’s home as 25 Menlove Gardens East the following evening at 7:30. It was, said Qualthrough, a matter of business.

Wallace slipped quietly into the club some time before eight. Beattie gave him the message and Wallace made a note in his diary.

The following evening Wallace arrived home shortly after six, had “high-tea” – a substantial meal – and left the house at a quarter-to-seven. He instructed his wife to bolt the back door after him, which was their usual practice. Julia Wallace, who was suffering from a heavy cold, nevertheless went with him to the back gate and watched him leave. Wallace walked to the tramcar, asked the conductor if it went to Menlove Gardens East and climbed aboard. The conductor advised him to change trams at Penny Lane and told Wallace where to get off. The conductor of the second tram advised him to get off at Menlove Gardens West.

Wallace slipped quietly into the club some time before eight. Beattie gave him the message and Wallace made a note in his diary.

The following evening Wallace arrived home shortly after six, had “high-tea” – a substantial meal – and left the house at a quarter-to-seven. He instructed his wife to bolt the back door after him, which was their usual practice. Julia Wallace, who was suffering from a heavy cold, nevertheless went with him to the back gate and watched him leave. Wallace walked to the tramcar, asked the conductor if it went to Menlove Gardens East and climbed aboard. The conductor advised him to change trams at Penny Lane and told Wallace where to get off. The conductor of the second tram advised him to get off at Menlove Gardens West.

Wallace now spent a frustrating half an hour or so trying to find Menlove Gardens East. Apparently it did not exist; although there was a Menlove North and a Menlove Gardens West. Wallace decided to call at 25 Menlove West just in case Beattie had taken down the address wrongly; but the householder there said he had never heard of a Mr. Qualtrough. Wallace tried calling at the house of his superintendent at the Prudential, a Mr. Joseph Crew, who lived nearby in Green Lane, but found no one at home. He asked a policeman the way, and remarked on the time; “It’s not eight o’ clock yet.” The policeman said “It’s quarter to.” He called in a general shop, then at the newsagents, where he borrowed a city directory, which seemed to prove that Menlove Gardens East did not exist. He even asked the proprietors to look in her accounts book to make sure that there was no such place. People were to remark later that Wallace seemed determined to make sure that people remembered him. Finally Wallace gave up and made his way home.

Wallace now spent a frustrating half an hour or so trying to find Menlove Gardens East. Apparently it did not exist; although there was a Menlove North and a Menlove Gardens West. Wallace decided to call at 25 Menlove West just in case Beattie had taken down the address wrongly; but the householder there said he had never heard of a Mr. Qualtrough. Wallace tried calling at the house of his superintendent at the Prudential, a Mr. Joseph Crew, who lived nearby in Green Lane, but found no one at home. He asked a policeman the way, and remarked on the time; “It’s not eight o’ clock yet.” The policeman said “It’s quarter to.” He called in a general shop, then at the newsagents, where he borrowed a city directory, which seemed to prove that Menlove Gardens East did not exist. He even asked the proprietors to look in her accounts book to make sure that there was no such place. People were to remark later that Wallace seemed determined to make sure that people remembered him. Finally Wallace gave up and made his way home.

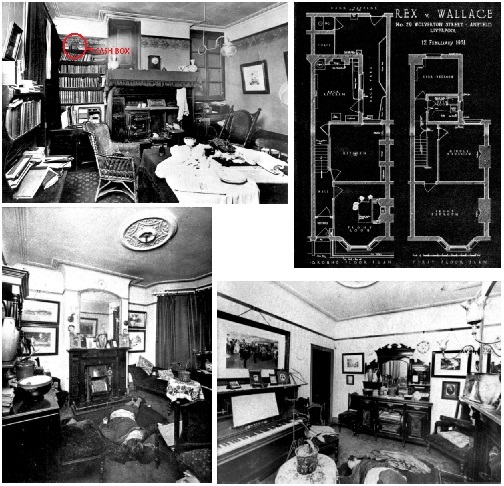

He arrived back at 8:45pm and inserted his key into the front door, to his surprise the door appeared to be locked on the inside. He tried the back door; that was also locked. Receiving no reply to his knocking, he called on his next door neighbours, the Johnstons, looking deeply concerned, and asked them if they had had heard anything unusual – only a thin partitioning wall separated the two properties. They said no and accompanied Wallace to his back door, where Wallace tried his key again and to his apparent surprise the door opened. Wallace entered the house whilst the Johnstons waited outside, moments later Wallace rushed out looking shocked and requested they follow him in stating “Come and see – she’s been killed”. They followed him into the house to discover Julie Wallace laying face down on the floor, there was a large gash to the back of her head, clearly indicating that she had been the victim of an attack, the room was splattered with blood. Later the Johnstons would comment on Wallace appearing curiously calm as he walked around the body to light the gas mantle. Wallace then suggested that the trio should head to the kitchen to look to see if anything had been taken. Here Wallace claimed that approximately four pounds had been stolen from a cash box. While John Johnston went to fetch the police, Florence Johnston stayed with Wallace, during this time Wallace made comment on the fact that Julie appeared to be lying on a mackintosh. It was later confirmed to be Wallaces own mackintosh.

When a police officer arrived Wallace explained he frantic and fruitless search for Qualtrough, as the police officer searched the home it was noted by Constable Williams that Wallace appeared “extraordinarily cool and calm”. The bedroom seemed to have be disturbed with pillows lying on the floor near the fireplace, however the drawers the dresser were all still closed.

He arrived back at 8:45pm and inserted his key into the front door, to his surprise the door appeared to be locked on the inside. He tried the back door; that was also locked. Receiving no reply to his knocking, he called on his next door neighbours, the Johnstons, looking deeply concerned, and asked them if they had had heard anything unusual – only a thin partitioning wall separated the two properties. They said no and accompanied Wallace to his back door, where Wallace tried his key again and to his apparent surprise the door opened. Wallace entered the house whilst the Johnstons waited outside, moments later Wallace rushed out looking shocked and requested they follow him in stating “Come and see – she’s been killed”. They followed him into the house to discover Julie Wallace laying face down on the floor, there was a large gash to the back of her head, clearly indicating that she had been the victim of an attack, the room was splattered with blood. Later the Johnstons would comment on Wallace appearing curiously calm as he walked around the body to light the gas mantle. Wallace then suggested that the trio should head to the kitchen to look to see if anything had been taken. Here Wallace claimed that approximately four pounds had been stolen from a cash box. While John Johnston went to fetch the police, Florence Johnston stayed with Wallace, during this time Wallace made comment on the fact that Julie appeared to be lying on a mackintosh. It was later confirmed to be Wallaces own mackintosh.

When a police officer arrived Wallace explained he frantic and fruitless search for Qualtrough, as the police officer searched the home it was noted by Constable Williams that Wallace appeared “extraordinarily cool and calm”. The bedroom seemed to have be disturbed with pillows lying on the floor near the fireplace, however the drawers the dresser were all still closed.

Another policeman arrivedjohnston and then shortly before ten o’clock, Professor of J.E.W. Macfall arrived, the forensic medicine concluded that Mrs. Wallace had died of a violent blow (or blows) to the back of the left hand side of her head and deuced she was likely sitting in the armchair and leaning forward as if talking to someone when she was struck. Once she had fallen to the floor the attacked had continued to strike her up to eleven more times.

Another policeman arrivedjohnston and then shortly before ten o’clock, Professor of J.E.W. Macfall arrived, the forensic medicine concluded that Mrs. Wallace had died of a violent blow (or blows) to the back of the left hand side of her head and deuced she was likely sitting in the armchair and leaning forward as if talking to someone when she was struck. Once she had fallen to the floor the attacked had continued to strike her up to eleven more times.

The Investigation:

Wallace made four voluntary statements but was never intensively questioned by the police, although he was required to attend CID headquarters every day and was asked specific questions about whether the Wallaces had a maid, why he had subsequently asked the man who had taken the telephone message at the chess club to be specific about the time he took it, and whether he had spoken to anyone in the street on his way back to his house from his abortive attempt to find Mr. Qualtrough. The police had evidence that the telephone box used by "Qualtrough" to make his call to the chess club was situated just 400 yards from Wallace's home, although the person in the café who took the call was quite certain it was not Wallace on the other end of the line. Nevertheless, the police began to suspect that "Qualtrough" and Wallace were the same man. Wallace's legal team conducted timing tests that showed it was possible for someone to have made the call, catch a tram and arrive at the chess club when Wallace did, and it was equally possible for Wallace to arrive at the same time by boarding at the stop he claimed he had used, nowhere near the telephone box. These tests were not introduced as evidence at trial since, ultimately, the Prosecution offered nothing to controvert Wallace's assertion that he had boarded the tram elsewhere, and did not make the phone call.

The police were also convinced that it would have been possible for Wallace to murder his wife and still have time to arrive at the spot where he boarded his tram. This they attempted to prove by having a fit young detective go through the motions of the murder and then sprint all the way to the tram stop, something an ailing 52-year-old Wallace probably could not have accomplished. The original assessment of the time of death, around 8 pm, was also later changed to just after 6 pm, although there was no additional evidence on which to base the earlier timing. A milk-boy witness who claimed to have spoken to Mrs. Wallace on her doorstep sometime after 6.30 pm further undermined the Prosecution case, leaving Wallace an extremely narrow window in which he could possibly have committed the "frenzied" crime, yet emerge blood-free and composed only minutes later to catch his tram.

Forensic examination of the crime scene had revealed that Julia's attacker was likely to have been heavily contaminated with her blood, given the brutal and frenzied nature of the assault. Wallace's suit, which he had been wearing on the night of the murder, was examined closely but no trace of bloodstains were found. The police formed the theory that a mackintosh, which was inexplicably found under Julia's corpse, had been used by a naked Wallace to shield himself from blood spatter while committing the crime. Examination of the bath and drains revealed that they had not been recently used, and there was no trace of blood there either, apart from a single tiny clot in the toilet pan, the origin of which could not be established, but was alleged to have been the result of inadvertent cross-contamination by the Police.

The Investigation:

Wallace made four voluntary statements but was never intensively questioned by the police, although he was required to attend CID headquarters every day and was asked specific questions about whether the Wallaces had a maid, why he had subsequently asked the man who had taken the telephone message at the chess club to be specific about the time he took it, and whether he had spoken to anyone in the street on his way back to his house from his abortive attempt to find Mr. Qualtrough. The police had evidence that the telephone box used by "Qualtrough" to make his call to the chess club was situated just 400 yards from Wallace's home, although the person in the café who took the call was quite certain it was not Wallace on the other end of the line. Nevertheless, the police began to suspect that "Qualtrough" and Wallace were the same man. Wallace's legal team conducted timing tests that showed it was possible for someone to have made the call, catch a tram and arrive at the chess club when Wallace did, and it was equally possible for Wallace to arrive at the same time by boarding at the stop he claimed he had used, nowhere near the telephone box. These tests were not introduced as evidence at trial since, ultimately, the Prosecution offered nothing to controvert Wallace's assertion that he had boarded the tram elsewhere, and did not make the phone call.

The police were also convinced that it would have been possible for Wallace to murder his wife and still have time to arrive at the spot where he boarded his tram. This they attempted to prove by having a fit young detective go through the motions of the murder and then sprint all the way to the tram stop, something an ailing 52-year-old Wallace probably could not have accomplished. The original assessment of the time of death, around 8 pm, was also later changed to just after 6 pm, although there was no additional evidence on which to base the earlier timing. A milk-boy witness who claimed to have spoken to Mrs. Wallace on her doorstep sometime after 6.30 pm further undermined the Prosecution case, leaving Wallace an extremely narrow window in which he could possibly have committed the "frenzied" crime, yet emerge blood-free and composed only minutes later to catch his tram.

Forensic examination of the crime scene had revealed that Julia's attacker was likely to have been heavily contaminated with her blood, given the brutal and frenzied nature of the assault. Wallace's suit, which he had been wearing on the night of the murder, was examined closely but no trace of bloodstains were found. The police formed the theory that a mackintosh, which was inexplicably found under Julia's corpse, had been used by a naked Wallace to shield himself from blood spatter while committing the crime. Examination of the bath and drains revealed that they had not been recently used, and there was no trace of blood there either, apart from a single tiny clot in the toilet pan, the origin of which could not be established, but was alleged to have been the result of inadvertent cross-contamination by the Police.

The Trial:

The Wallace trial began 22nd April 1931, before Mr Justice Wright. The prosecutions case was that Wallace had concocted an elaborate plan to murder his wife, and had phoned the café to make the appointment with Qualtrough on the evening before the murder. The endless and elaborate enquires about Menlove Gardens East were intended to provide him with a perfect alibi; but Mrs Wallace was already dead lying in her sitting room when William Herbert Wallace left the house. In the closing speech for the crown Mr E. G. Hemmerde made much of the “inherent improbabilities” in Wallaces story: that surely an insurance agent would not spend his evening on such a wild goose chase. He also made much of Wallace’s apparent calmness immediately after the discovery of his wife’s body. The judges summing up was favourable to Wallace and there was some surprise that after only an hour, the jury returned a verdict of guilty. F. J. Salfeld, who was present in the courtroom, later commented, "what probably harmed most at his trial was his extraordinary composure. Like every other observer, I found enigmatic his seeming indifference to his surroundings. Shock? Callousness? Stoicism? Confidence? We shall never know."

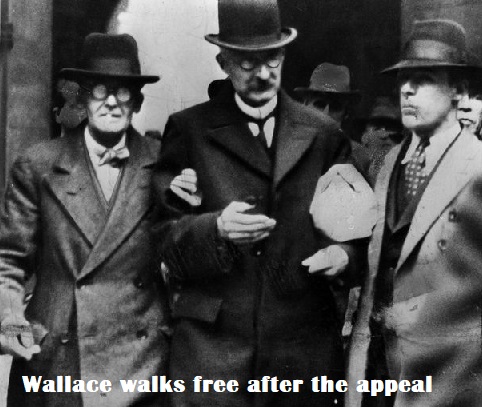

In an unprecedented move, in May 1931 the Court of Criminal Appeal quashed the verdict on the grounds that it "cannot be supported, having regard to the evidence", and Wallace was set free. The decision meant that the jury was wrong in law, and in fact there was no evidence against Wallace—appeals are usually brought on the basis of bad decisions by the presiding judge at the original trial, or by the emergence of new evidence.

No other person was charged with the murder and it remains officially unsolved. A further mock-trial, conducted by the Merseyside Medico-Legal Society in 1977, presided over by Mr. Justice Lawton, also found Wallace not guilty. Robert Montgomery QC led for the Prosecution while Richard Whittington-Egan led for the Defence.

The Trial:

The Wallace trial began 22nd April 1931, before Mr Justice Wright. The prosecutions case was that Wallace had concocted an elaborate plan to murder his wife, and had phoned the café to make the appointment with Qualtrough on the evening before the murder. The endless and elaborate enquires about Menlove Gardens East were intended to provide him with a perfect alibi; but Mrs Wallace was already dead lying in her sitting room when William Herbert Wallace left the house. In the closing speech for the crown Mr E. G. Hemmerde made much of the “inherent improbabilities” in Wallaces story: that surely an insurance agent would not spend his evening on such a wild goose chase. He also made much of Wallace’s apparent calmness immediately after the discovery of his wife’s body. The judges summing up was favourable to Wallace and there was some surprise that after only an hour, the jury returned a verdict of guilty. F. J. Salfeld, who was present in the courtroom, later commented, "what probably harmed most at his trial was his extraordinary composure. Like every other observer, I found enigmatic his seeming indifference to his surroundings. Shock? Callousness? Stoicism? Confidence? We shall never know."

In an unprecedented move, in May 1931 the Court of Criminal Appeal quashed the verdict on the grounds that it "cannot be supported, having regard to the evidence", and Wallace was set free. The decision meant that the jury was wrong in law, and in fact there was no evidence against Wallace—appeals are usually brought on the basis of bad decisions by the presiding judge at the original trial, or by the emergence of new evidence.